What can get people thinking more than a confrontation with contradictions?

Ronald Kodritsch | Posted on |

Text for “Bastards” by Dr. Ursula Mähner-Ehrig

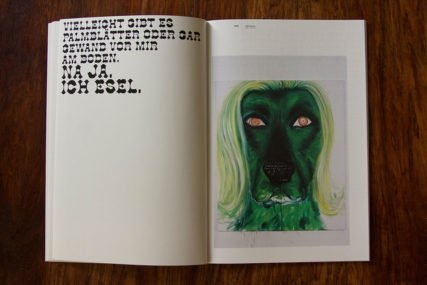

With his 'Bastards' series Ronald Kodritsch has managed to strike a raw nerve. In his series of dogs wearing wigs he uses the repertoire of alienation to make what has been made come together with what has naturally grown, to make artificiality meet nature, to juxtapose the fake with the genuine. Artistic hairdos created by people encounter the coats of fur that grow on animals.

The result is not without a certain sense of humour. The humour in this work is there to help viewers optimise their pleasure, as it were. But not just that; we're surprised at the flood of associations which come to mind: nature and artificiality, the man and animal relationship, the misuse of the dog as a domesticated animal, as a means of gaining a supply of narcissism, as an extension of or supplement to our own selves, but also as a kind of mimicry of the dog, the sight of whose portrait triggers the association of 'striking features' in the viewer. What we have taking place here is the external changing the internal.

We can associate the 'wig' with the hairpieces so much in fashion in the 1970s, with part of the insignia of a particular profession (e.g. the wigs worn by British judges), with status symbols of the baroque and rococo periods which were de rigueur in order to appear at court or in town when nature was considered too coarse and unrefined to be socially acceptable.

Above and beyond an intellectual analysis of the portraits of Ronald Kodritsch's 'Bastards', what impresses is the way the dogs look directly at the viewer. Some have sadness in their eyes while others appear to gaze sharply with narrowed pupils; still others in turn glance helplessly from under the strange thing on their head. There's even a cute little side glance. Some dogs exude self-conviction - their hairdo appears to have grown from their own hair and no longer seems to be a wig at all. Then there are the empty eyes, i.e. no look at all, a 'zero look' as it were, of the Halloween 'bastard', whose eyes are as hollow as those of a Halloween pumpkin; but even so, it is taken from everyday life: the creature is carrying a shopping bag with a Halloween logo: advertising, as we know, seems to gets everywhere.

And then these images start to get us thinking: sometimes we have the impression of looking straight into Ronald's big brown eyes. It is as if this look can see right through to the bottom of things: the alienation of man from nature, and even from his own nature; or the manipulation of nature which in the case of these dogs is made possible through their social conditioning that makes them the subjects of man, their master. The animal loses its dignity after being manipulated in such ways. But every now and again quintessential dogginess rears up, as when the dogs' pointed ears poke up through the wig.

As an artist – and society gives him every right to do so -Kodritsch permits himself the liberty of dispensing with words and using the means of alienation to generate humour and laughter. By doing so, he tempts the viewer into engaging with the serious aspects of the sub-message conveyed in his pictures. He manages to do this because we are gladly prepared to follow him: after all, jokes, comedy and humour save time and effort in the economy of the mind. By acting as a shortcut to the laborious learning path of mental activity and take us straight back to 'the mood of a time in our lives when we would engage in mental activity with a minimum of effort if at all, the mood of our childhood when we did not as yet recognise humour, were incapable of making a joke and did not need humour to feel happy in life.' (cf. Freud, 1905). Max Reinhard put it in a similar way. The artist, he believed - he was actually talking about actors - was one of those people who shoved a piece of childhood in their pockets and mysteriously stole away from the gaze of others. As long as they are accompanied by humour, contradictions are more tolerable than brutish finger-wagging seriousness.

Sigmund Freud, 'The Joke and its Relation to the Unconscious' in: Collected Works, Vol VI, p. 269 (German edition)

Dresden, den 11.02. 2008-02-11

Dr. Ursula Mähner-Ehrig, Psychoanalytikerin, Wien

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.